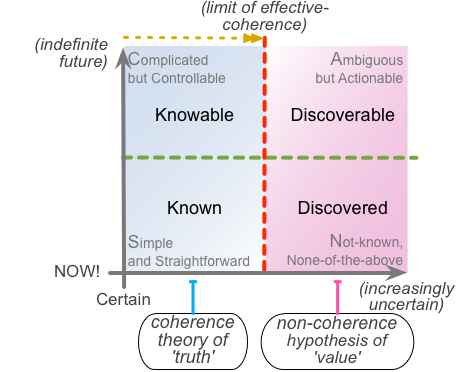

3 A Case for CorrespondenceĬhristian philosopher J.P. To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true so that he who says anything that it is, or that it is not, will say either what is true or what is false. Easy enough, right? Aristotle put it this way: And statement 3 is true if elective abortion really does kill an innocent human being. Statement 2 is true if, in fact, the city of Los Angeles is located in California. Statement number 1 is true if, in reality, Donald Trump is the current President of the United States. Elective abortion kills an innocent human being.Īre these statements true? They are if, in fact, they match reality.The city of Los Angeles is located in California.Donald Trump is the current President of the United States.When the truth-bearer (an idea) matches the truth-maker (reality), they are said to stand in an “appropriate correspondence relationship,” and truth obtains. In this sense, reality is the truth-maker, and the idea, belief, or statement is the truth-bearer. The correspondence theory of truth states that an idea, belief, or statement is true if it matches, or corresponds with, reality. While not taught explicitly in Scripture, it is assumed throughout both the Old and New Testaments. This may rightly be labeled the “common sense” view of truth. It is a necessary condition for truth but by itself is not sufficient.įinally, there is the correspondence theory of truth: truth is when an idea, belief, or statement matches (or corresponds with) the way the world actually is (reality). But most people intuitively understand that truth has something to do with the way the world really is.Ĭoherence is important but not enough. What is true is not what matches reality but rather what coheres within a given system of belief. The reason is that the coherence theory cuts the knower off from the real world. Problem #3: This view, like the pragmatic view, seems counterintuitive. But relativism is false therefore, like the pragmatic view, the coherence theory must be rejected. Two contradictory beliefs may both be “true” as long as they cohere with their respective systems. On the coherence view, what is true is relative to each individual’s belief system. Problem #2: For the same reasons as problem #1, and like the pragmatic view, this view implies relativism. This leads to the absurd notion that contradictory propositions can both be true. On this view, it is possible for two different people to hold contradictory beliefs yet for both beliefs to be “true” as long as these beliefs cohere with each individual’s web of belief respectively. Problem #1: This view implies that contradictory propositions can be true. Three major problems with this view are as follows: Second, there is the coherence theory of truth: truth is logical consistency (coherence) among a set of beliefs an individual holds. But if that is the case, then truth is relative, a view which itself is untenable and self-refuting. On the pragmatic view, as long as these contradictory beliefs are useful for the respective individuals who hold them, we would have to conclude they are both true. Imagine two individuals who hold contradictory beliefs. If truth is what works, then the pragmatic theory itself must not be true, since most philosophers throughout the ages have not held to the pragmatic theory (i.e., it didn’t “work” for them) but rather have found the correspondence theory to be much more useful! For example, there are some true beliefs which are not very useful (e.g., the belief that my cat has grey and white fur), and some false beliefs which may turn out to be very useful (e.g., my false belief that people actually read my articles is useful motivation to continue writing them). Problem #1: The view seems counterintuitive. Historically, there have been three dominant theories of truth put forth by philosophers: 1įirst, there is the pragmatic theory of truth: truth is what works. But this is easily remedied if we take a few moments to reflect on the nature of truth. In other words, we may not be confident in our knowledge of what truth is because we struggle to articulate a definition.

Perhaps the problem is not that we do not know what truth is but rather that we do not know that we know. I say that because we presuppose a certain definition of truth in our speech and actions every day of our lives.

In reality, I think we all know the answer to this age-old inquiry. The question, at first blush, may sound profound. “What is truth?” Pontius Pilate wasn’t the first, or the last, to ask this.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)